Why Washington Needs to Think Greek: Charles Edel on the Lost Sense of the Tragic

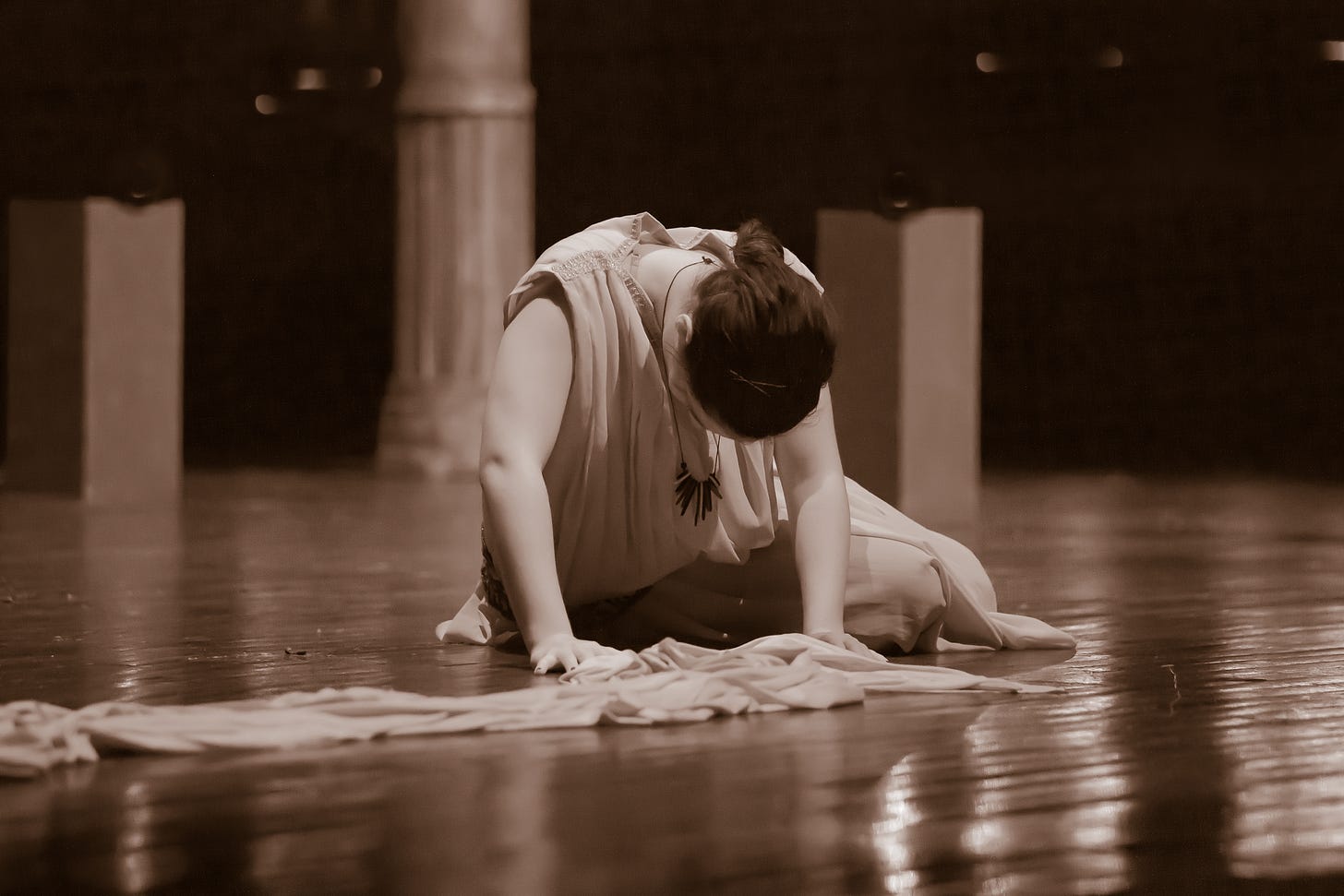

Ancient Greek theater showed leaders "fall due to errors, ignorance, hubris. By understanding how bad things could get could get, Athenians made sure to prevent that from happening in real life."

In their 2019 book, The Lessons of Tragedy, Charles Edel and Hal Brands explore a value that has long been absent from most American thought: a sense for the tragic. As Edel and Brands point out, that awareness, though neglected today, has never been more relevant. We spoke with Edel, a former State Department official now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, about the book and what he thinks the United States could learn from the ancient Athenians and their dramas. What follows is an argument for why the work of Sophocles, Aeschylus, Euripides and their ilk remain necessary today—and have implications for domestic politics and international affairs, not just literature and the theater.

If you like the interview and are interested in more, please subscribe to our weekly Substack, WHY THE CLASSICS?, by clicking here. And for more smart coverage of the arts, economics, and international affairs, check out our magazine, available online and in print.

In his interview with The Octavian Report, Edel said that he and Brands were motivated to write their book by the fact that, for centuries, most American leaders and policymakers have assumed that U.S. history is the story of unidirectional, uninterrupted progress. Today that notion has become very difficult to sustain—but the thinking hasn’t necessarily changed.

“One of the recurring conversations that Hal and I had,” Edel said, “was that history seemed too often to be missing from the larger U.S. policy debate. The idea that we seem to be on a path to progress, world betterment, and increasing stability—this was ahistorical, totally out of step with the recurrent cycles in history. As we discussed this, we realized that tragedy was a really useful way to frame and talk about international relations.”

Why is a sense of the tragic so important? The reason, in Edel’s telling, is because it forces people to accept their worst fears might become reality. Admitting this, Edel argues, needn’t lead to paralysis. Just the opposite: it should provide the motivation to undertake truly extraordinary feats in the hoping of saving the situation.

No one knew this better than the Athenians of the early 6th and 5th Centuries BCE, for whom tragedy was an integral part of life. “The Great Dionysia was the festival where you would go to watch tragedy,” Edel told us. “Citizens would gather once a year for about three days. It would be a public holiday. They would watch these performances, which were subsidized by the state. You would have the entire community there to watch. All the citizens would come into the theater, but reserved in the front row would be seats for the ten generals elected from the people. They would march the war widows and orphans in and give them seats of honor. Every resident alien and ambassador would be there as well, to be awed by the splendor and majesty of Athens. Then they would turn their eyes [toward the stage], and watch prominent individuals fall due to errors, due to ignorance, due to their own acts of hubris. Only by understanding how bad things could get, how quickly things could spiral out of control, could the Athenians make sure that they worked as individuals and as a community to prevent what they just saw on the stage from happening in real life.”

No ancient work bears clearer testament to this idea than The Peloponnesian War, by the historian Thucydides. “The book is stage-managed like a tragedy,” Edel said. “There are actors, there are speeches, there’s dramatic parallelism. Consider the greatest speech in the book, the funeral oration given by Pericles: a call to communal sacrifice, to be forward in defense of the nation. Of course, the very next scene is the plague that falls on Athens. Having listened to Pericles’s stirring words, the Athenians do the exact opposite [of what he recommends], and not only die in great numbers, but are chewed out by their leader for not following his wise advice. The point, I think, is that this is meant to be just as instructive as the plays were. That it is almost—almost—impossible not to let your logic and your reason be overwhelmed by your passions.”

Fast forward a couple millennia to the First and Second World Wars, which were paradigmatic examples of Thucydidean tragedy. Edel argues that these conflicts had a commensurate effect on the United States’ political leadership. “The American project, the American-led order, the rules-based order, the liberal international order—whatever we want to call it—is definitively what America took the lead on doing in the aftermath of World War II in order to make sure [the Allies] didn’t repeat the failed lessons of what they had done after World War I. Harry Truman made the call, and he appealed directly to many of the young men and women who had participated in those wars by saying, effectively, ‘We’re asking you to take these actions and efforts during peacetime to make sure that we don’t return to what we just went through over the last 15 years.’

“That immediately resonated. It was never an easy sell, but it was politically palatable and acceptable in its broad contours by both parties. And I think it’s important to point out that while [the result] has not been perfect, it produced amazing success. Global prosperity dramatically increased. There hasn’t been another great power war, although there have been many bloody proxy wars. We went from a dozen or so democracies in the aftermath World War II to more than 80, even if they’ve recently begun to recede.”

So how, where, and why did Americans lose sight of the Athenian values that inspired the postwar project? One explanation, according to Edel, lies in the paradoxical fact that great success bred by hardship conceals the sources of its own conception.

When he and Brands started looking at the current state of international affairs, they realized that “the idea that things can go horribly wrong, which inspired America to take the efforts and exertions that it did in the first place, seems to have gone missing, probably because it’s been so long since we experienced a real and profound international tragedy,” Edel says. “Indeed, the problem with success it that it tends to breed complacency, and the postwar order that America labored so hard for has been undercut by its own success. It’s been more than 70 years since World War II, it’s been 30-odd years since the end of the Cold War, and that’s led many observers to think that the prospect of global conflict and a true buckling of the international order is actually an impossibility. That [complacency] has led to a slackening of not only the desire but also the willingness to pay for some of these large efforts that underlie the order. Worse still, this has happened just at the time when the international environment is becoming more fraught.”

As for the popular notion that the United States is declining just as the world is becoming less stable, Edel says that it’s important to distinguish between an Athenian sense for the tragic and simple pessimism. Pessimism is enervating and leads to fatalism, while tragedy spurs people to action by reminding them that while the worst might occur, they can still prevent it by fighting hard. The Greek tragedies, Edel points out, “have real communal messages about sacrifice, about resolve, and about struggle, even when you don’t know the outcome and can’t possibly know the outcome. About mustering the courage to take action together. Even when you’re faced with no good choices.”

Tragedy has no time for anxiety over permanent decline. Nor is it warranted by contemporary data, Edel says. “America is still doing pretty well. Until recently, we had not only good demographics, but favorable immigration policies. If you look at the size of the economy, the GDP was roughly 22 percent of 2016 global GDP, which is not far off the highs of the 1970s. When you begin to add in allies and partners, we’re talking about upwards of 60 percent of global GDP and military outlays, which is far in excess of any competitor.

What troubles Edel are not the facts but how Americans interpret them. “Since the end of the Cold War and the disappearance of our major strategic competitor,” he says, “American policymakers’ strategic muscle memory has faded because they haven’t had to hone it quite as sharply as they did previously. It’s coming back, but it has faded as no challenge seemed to emerge from a true competitor on a global scale.”

But today the United States does have an emerging competitor: China. Edel notes that Chinese President Xi Jinping is one of the few current global leaders to have deeply imbibed the teachings of tragedy. “It is a core narrative of the People’s Republic of China under Xi that the Chinese know how bad things could get because they’ve experienced it. They’ve experienced 150 years of humiliation. I do think there is a willingness in China to undergo common hardship for national ends. They keep their history very close to them.”

Meanwhile, Americans’ amnesia about their own past tragedies, Edel argues, has given fuel to the current crisis of liberalism as a philosophy and democracy as a political system. “When democracy is seen to not provide for its own citizens’ needs,” Edel says, “people are more willing to believe in alternative systems and purveyors of different truths. In some ways, that is the lesson of the 1930s. Economic crisis begets political crisis begets global crisis. We also have not had to make the argument to our own citizens and to different countries around the world about why our system is better—or if it indeed is better. This has been for too long assumed because you couldn’t point to any alternative models and examples. I think we’re in the process of waking up to the fact that those benign conditions no longer exist. There are different systems competing with democracy. That’s true both internationally and domestically. If our system is not seen as promoting the best interests of a great majority of our citizens, people become less enamored of it.”

On the question of whether the United States can surmount its problems, Edel is guardedly optimistic. “America has the resources and abilities—particularly the ability to lock arms with its allies and partners—to deal with the challenges that we face today,” he says. “It is a question of willingness, and above all willingness during peacetime, which makes it more challenging politically.”

One way to spur that willingness is through reading. “I would really recommend Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way, a scan of Greek culture,” he says. “I would also put front and center [former U.S. Secretary of State] Dean Acheson’s Present at the Creation, which describes both the lessons that he and others thought they had learned from the 1920s and 1930s, and exactly what they were trying to do as they stumbled their way forward. Acheson was a contemporary of Gen. George C. Marshall, who said that you could not possibly understand what was happening in the unfolding Cold War if you had not read your Thucydides.”

“Finally, there are the Federalist Papers,” Edel added. “They are steeped in the ancient classics, with multiple references to small democratic and republican states and how they failed. They are also deeply interested in national security and foreign policy. In fact, the spurs to the Constitution were foreign policy crises. The argument that both Alexander Hamilton and James Madison dig into is that we need to look back to the ancients because one has to be a pretty gloomy-minded (but not pessimistic) person to understand the world we’re living in. Absent that, you have no chance to create something that is not only new, but that has a chance of sustaining itself.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.