Gonzo Painting: Julian Bell on Van Gogh's "Night Café"

“A place where you can ruin yourself, go mad, commit crimes.”

Vincent Van Gogh is remembered today for his extraordinary inventiveness, his almost sculptural brushstrokes, the thrumming intensity of his colors, and his tragic life story (he committed suicide at 37). What he’s not known as is a storyteller or a writer. But he was all those things. The author of more than six hundred letters to his brother Theo, van Gogh’s legacy lives on in ink on paper as well as paint on canvas. Few understand these different sides of the artist better than Julian Bell; as both a writer—his books include Van Gogh: A Power Seething—and a painter himself, he straddles both worlds. In the essay below, he takes on one of van Gogh’s most narrative works, the influences that shaped it, and the ideas that informed The Night Café, the “crazy Dutchman’s” modernist masterpiece.

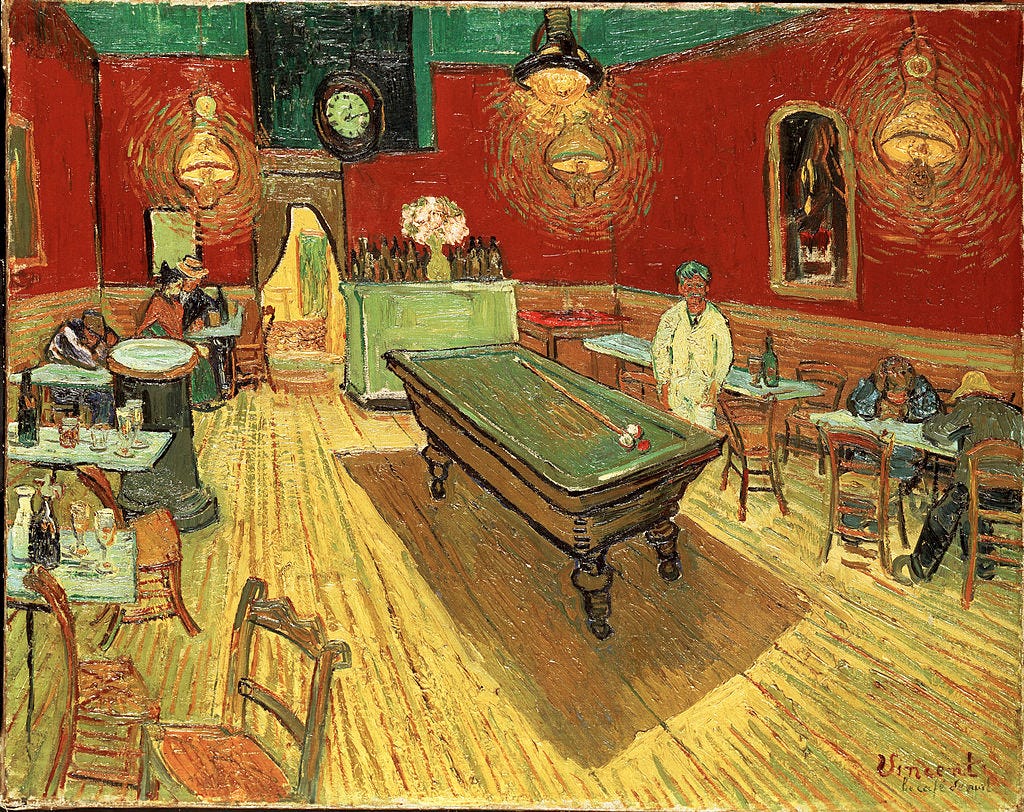

When people call a painting “literary,” they rarely speak in high praise. Good taste and standard modernist wisdom tell us that paint should make us think about paint and not about the things poets and novelists get up to. But when—as someone trying to hold together both disciplines, writing on a keyboard spattered with ultramarine and umber—I want to seek an example of literary painting that will take me to the form's furthest reaches, I head for the Yale University Art Gallery, where Vincent van Gogh’s The Night Café holds pride of place.

The three-foot-wide canvas in an ornately encrusted belle époque frame is coarsely woven and is crusted with upraised gouts of color: this is as uncompromisingly concrete an object as any oil painting can be, or at least as any could be when it was executed in 1888. Before the canvas communicates color, composition, or any form of meaning, it comes forward as rugged physical fact. But what furious purpose there is to all the hefty paint-paving: each streak and stud obeys the confines of a decisive perspectival structure, and driving those drawn outlines is an equally decisive project. It is in this project that The Night Café is eminently literary.

To push description forward into every corner of modern society; to find ways to speak, not just of its seemly mainstream, but of its nobodies, its nowheres, and unexamined in-betweens: that was the agenda launched by Charles Dickens and Émile Zola, the novelists Vincent most admired. In their wake, in the later 19th century, undercover journalism was getting going: reporters posing as vagrants to investigate flophouses, or colluding in trafficking for the sake of an exposé. In like spirit, here was Vincent, the hugely well-read, irrepressibly articulate son of a provincial parson, committing himself to spend three whole September nights awake—dozing by day—so as to bring back from the small hours a visual account of one of the seediest dives in Arles, with what he called its cast of “sleeping ruffians.” The café called for description exactly because it was so ugly. Its urban lowlife would complement the images of peasants, gypsy caravans, railways, and parks he was concurrently at work on. I think what he was aiming for, in the supremely productive summer of 1888, was a social panorama equivalent to Balzac’s Comédie humaine.

To be sure, between undercover and gonzo journalism—the reporter going native—the line gets hard to draw. Whatever town he pitched up in, Vincent liked to head for the scruffy transit zone. Establishments such as this Café de la Gare appealed to him because the absinthe was cheap and so were the likes of the woman with the client in the painting's left-hand corner. He was in fact currently lodging just upstairs. Had he gravitated towards his own natural milieu? Yes and no. He liked to think he was friends with the café’s proprietor, Joseph Ginoux—the white-clad figure inserted (strangely minus his legs) behind the billiard table. But five months later, Ginoux would be one of the local signatories to a petition calling for the crazy Dutchman to be deported from Arles.

In fact, a tug of war between immersion and dissociation dictates the whole composition. At once the viewer is plunged into the hot stale fug of the all-nighter, the viscid paint rendering it intensely actual. At the same time, the perspective hurtles away, and they—the “ruffians”—are at an unbridgeable, alien remove. They have to be. In Vincent’s literary imagination, the café becomes “a place where you can ruin yourself, go mad, commit crimes.” The panorama he was aiming for was not just social, but spiritual: he also linked this painting, in letters to his brother Theo, with his picture of The Sower—an image of redemption to match an image of damnation.

Vincent spoke of both pictures as “exaggerated.” This, he knew, was his own original variation on the practice of his avant-garde contemporaries: to push the painting of the observed world beyond realism, to intensify the brushwork and the color scheme to such a degree that the viewer would be pitched irresistibly into a distinct emotional state. Hence Vincent’s most famous claim about The Night Café, his supreme assertion of literary intention: “I’ve tried to express the terrible human passions with the red and the green.”

That statement has been so often quoted that we no longer look it in the eye. So allow me to ask: did Vincent’s attempt to express the passions succeed? Isn’t this the point at which literature hits its limits? In researching my biography of Vincent, I came across a wonderfully laconic comment from one of the few acquaintances of this impossible character who got on well with him, saw the point of him, but at the same time wasn’t in any way in awe of him: a man called Andries Bonger, a stockbroker friend and eventual brother-in-law of Theo’s. “Dries” wrote to Theo from Paris that Vincent had been showing him some flower-pieces of his. Dries thought they looked too “flat.” But Vincent had been giving him the spiel, all about how he “wanted to get this or that color contrast into it.” And Dries added: “As if I gave a damn what he wanted to do!”

Exactly! Never trust what painters claim they’re attempting. Test out your own visual responses to the object created, and shut your ears to the rest. Doing so in the Yale University Art Gallery, I experience a sumptuous, heavy, dissonant yet weirdly delicious orchestration of colors, pivoting on the keynote of the pale green bar stand. (As you see, my phraseology, leaving off literature, has switched for support to music instead.) The empty glasses and the gas-lamp glare make me think of some dreary joints I’ve holed up in, but I cannot claim that the red and green have planted thoughts of crime and ruination in my mind. Yes, Vincent, I want to argue, color feels—it is generically analogous to emotion—but no, Vincent, color doesn’t mean, in the way that literary utterances do.

Vincent was a terrier when it came to any verbal tussle, and I’m sure he’d have pulled me to the ground on that one. Yet I like to imagine that secretly, he might have agreed that it was the attempt to express that mattered, not the success in doing so. Ten days after painting The Night Café, he was turning his own argument almost perversely round on himself, in a letter to Theo: “It always seems to me that poetry is more terrible than painting, although painting is dirtier and more damned annoying, in fact. And after all, the painter says nothing; he keeps quiet, and I like that even better.”