When DOGE was HUAC: The rise and fall of the Federal Theatre Project

Columbia's James Shapiro on how the US Federal Theatre changed culture and made the wrong enemies

The Octavian Report has returned to Substack!! In these chaotic times, we hope our trademark blend of foreign policy, economics, culture, and ideas is both illuminating and refreshing. Our readership tells us it’s needed now more than ever. As we “relaunch,” please do share us with anyone you think will enjoy our unique content and help us grow our community of free thinkers, of tolerance, of quality, and of quirkiness.

We kick off with a return performance from James Shapiro, Columbia professor, best-selling author, and one of America’s top experts on Shakespeare. With the DOGE at full blast, federal funding for the arts is once again in the crosshairs, with the heads of PBS and NPR summoned to hearings in the House of Representatives next month by Marjorie Taylor Greene, today’s analogue of the first HUAC chairman, Martin Dies.

In our conversation, Shapiro tells the suddenly incredibly timely story of the Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal-era program whose history he covers in his excellent book, The Playbook: A Story of Theater, Democracy, and the Making of a Culture War, and which highlights another dramatic moment when the tension between the arts and government funding also boiled over. The Federal Theatre pushed enough barriers to give Orson Welles and Arthur Miller their starts and staged productions still talked about, but also crossed political lines that led to its own demise and made it the first casualty of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

The success and then ultimate failure of its delicate balancing act is as relevant as ever for anyone who cares about our national culture and a cautionary tale worth remembering as we once again take up this debate.

Opening night of Macbeth, April 14, 1936, Lafayette Theater, Harlem

Octavian Report: Why did you decide to write a book about the Federal Theatre?

James Shapiro: COVID had just struck and I realized that I was going to be spending a lot of time writing and trying to stay alive like everybody else in New York. My first impulse was to go back to the plague of 1592 to 1594 in Shakespeare's London and write a book about that. I then realized when this plague ends, no one is ever going to want to read a book or think about plague or COVID again.

So I parked that on the side and thought, what else interests me and do I care about? I've been working for the past 15 years with theaters, advising productions. During COVID theaters were going under and the ways in which theaters had become part of daily life in America was even more eroded. Theaters have never bounced back from COVID.

The thought of the place of theater in democracy sent me back to looking into the history of the two of them and, as I say in the book, there's a reason why both democracy and theaters were created in ancient Athens. They're mutually sustaining. And I thought about the ways in which a healthy democracy needed a healthy theater and a healthy theater needed a strong democracy.

And that sent me into the archives to start looking at the history of the Federal Theatre. And I was surprised to learn that from 1935 until 1939 in the United States we had a government sponsored theater. And it reached 27 states. They staged over a thousand productions that reached an incredible number of Americans, just a staggering percentage. One out of every four Americans or so, two-thirds of whom had never seen a live play before. And it put 12,000 actors and directors and playwrights and stagehands back to work.

“There's a reason why both democracy and theaters were created in ancient Athens. They're mutually sustaining.”

This was part of the WPA program to employ those who during the Great Depression were out of work. And you had to be on the dole, so to speak, to be eligible to be part of the Federal Theatre. Luckily for us, talents like Arthur Miller and Orson Welles and Burt Lancaster were all on the dole and got their start through the Federal Theatre. It was an extraordinary moment in our country's history, one in which the government still believed that the arts, as much as agriculture or industry, were necessary for the health of the country and deserved federal support.

OR: You do a great job bringing to life some of these productions in the book. You start with the famous “Voodoo Macbeth” which, if I recall, was Orson Welles’ first directing job?

Shapiro: It was, aside from his schoolboy productions at boarding school. It was a mind-blowing success. It came on the heels of failure. One of the first major Federal Theatre plays was called Ethiopia. Hundreds of people were working on it. The whole idea was not to have a two-hander or a four-hander, but to put 100 or 200 people on stage so you were employing as many people as you could. Especially in places like New York. So a Broadway theater was booked.

The play about Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia was rehearsed and ready for production. And it was going to be amazing. It was going to be politically edgy. It had a largely African troop of drummers and singers stuck in the US who were going to play the Ethiopians. So you had a mixed race cast at a time when Broadway did not have that except for maybe musicals like Showboat.

Somebody wrote to Washington, D.C. asking for an audio clip of FDR speaking about Ethiopia. The State Department caught wind of this and freaked out and said, you can't do this play. It interferes in American foreign affairs at a time when we were trying to placate Mussolini and the fascists. So the plug was pulled after one dress rehearsal.

But they still had these African actors. They shipped them uptown to the Lafayette Theater in Harlem where there was a so-called “Negro Unit.” There were twenty Negro Units across the country set up to develop African-American talent, which was largely untapped and unrealized in the theater world at this time. John Houseman, who later went on to great fame, was brought in to work with leading black directors. Rose McClendon was in charge of the Lafayette unit. She died and Houseman stepped in.

He brought in his young friend, actor Orson Welles, and said, do whatever classical play you want. Welles knew Shakespeare as well as anybody in the world at that point, although he was only twenty years old. So he worked with this company of 150 black actors, musicians and performers.

Macbeth then was so stale. It was the usual, plaid with bad Scottish accents. New Yorkers had seen a Macbeth pretty much every year since the turn of the century but the play was lifeless. By using voodoo as opposed to European 16th-century witchcraft, it made it feel real. And there was a lot of talent on that stage. The play was a huge hit.

“Orson Welles said it was the best thing he'd ever done in his career”

Whites came up from downtown, from the Village to see it. It was such a success that Hallie Flanagan, a Vassar professor who was in charge of the Federal Theatre, decided to rent six railway cars and put it on the road from Connecticut to Jim Crow Dallas. This production was the greatest Shakespeare tour in American Shakespeare history.

The problem with writing about theater is unlike film, it disappears. There is a four-minute clip of the “Voodoo Macbeth” you can look at on YouTube. But it doesn't capture the political impact, the social impact on Harlem. Film is preserved, plays die. So it was very important for me in The Playbook to try to bring to life these productions in a way that, to use a cliché, makes you feel you are there. You are in the audience. You're part of the excitement. As people at the Lafayette Theater gathered outside, the police had to keep them at bay. The excitement was incredible. The audience came on stage after opening night. Orson Welles said it was the best thing he'd ever done in his career many years later.

I think these are stories that have to be told and remind us about the ways in which theater acts as a catalyst for social change. Which is threatening to some, but to my mind, good for the health of the Republic.

Octavian Report: A lot of the shows in the book seem to take on controversial topics, race, labor, politics. Was this a lot of what the Federal Theatre put on?

Shapiro: I could have written about Christmas plays. I could have written about Yiddish plays, German, French, Spanish-immigrant plays that were being done, They did everything. They did Moliere. They did Scandinavian plays. They did bad American plays. Ninety percent of those thousand productions were innocuous. They included Burt Lancaster doing trapeze or weightlifting. A lot of these were kids’ plays. They would take trucks and drive around to schoolyards, pop open and do plays for kids.

This was the Depression. Nobody had money. So this was for free or for a nickel. But my book does focus on the political because half the book is on the political pushback to the Federal Theatre. These other ten percent of plays were progressive politically. The problem is theater, whether it's Oedipus or Shakespeare or Voodoo Macbeth, inevitably tries to change the status quo. And there are people who like the status quo and will resist any efforts to change it.

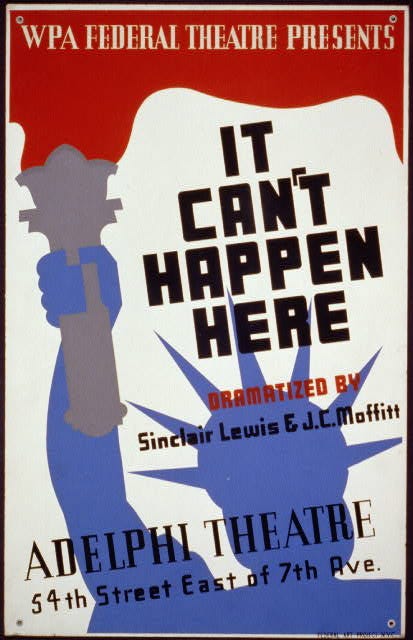

Let me talk about It Can't Happen Here [based on the Sinclair Lewis novel about American fascism] because that production encapsulates something that was essential to American culture at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1900, there were literally hundreds of touring acting companies going around the country thanks to the expansion of the railroads. Small towns in America had one, sometimes more than one, theater. There was a thick book that anybody in the theater world could buy that was revised every year that told you where to stay in this small town in Oklahoma or Tennessee, the size of the theater, the number of seats, the lighting. And a company could just tour across the country. And major stars did so as well as local companies. So theater was, in the early 20th century, a major cultural force in this country.

It died almost overnight when the movies came. The movies were able to provide entertainment far less expensively. All those theaters were turned into movie houses. So by the time you got to the Twenties and Thirties, you had a lot of unemployed actors who couldn't transition to film.

It Can't Happen Here was an incredibly popular novel written in the 30s by Sinclair Lewis, whose wife Dorothy Thompson was a leading journalist and one of the first to interview Adolf Hitler. She came back and said, “It's going to happen here. We're going to have a dictatorship.”

Lewis sat down in their Vermont home and quickly wrote this novel. His last two novels had been made into million-dollar Hollywood films that made a lot of money. Hollywood bought it and they cast some of the best actors in the country.

The premise of the novel is that America is taken over by a fascistic president who decides to create camps to lock up immigrants. I know this is all hard to imagine, but this is the fear and fantasy of it can't happen here….

But Hollywood in the end pulled a plug on it. Sinclair Lewis was angry. Hallie Flanagan came to him and said the Federal Theatre would not only take the show, but mount it in every city the same day, opening like a movie does. Everywhere simultaneously. And it would allow each locality to subtly change it so that it spoke to that region. All of a sudden, you had theater doing what film couldn't do. And fighting back against film.

“Hallie Flanagan said the Federal Theatre would mount the show in every city the same day, opening like a movie does.”

In twenty or so locales, the play opened at the same time. In Yiddish in New York. And of course in English on Broadway. In Spanish in Florida. All over the country, this thing just hit like a ton of bricks. And of course, those who kind of lean towards fascism were not all that happy with a play that showed Americans embracing dictatorship.

Octavian Report: So I don't think it's a spoiler since you open the book with the hearings, but why did the Federal Theatre become the first casualty of the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee?

Shapiro: It didn't have to turn out this way. Just to set the facts straight. In the summer of 1939, the Federal Theatre, which had been created in 1935, was permanently closed. Just like that. Productions had to just throw away costumes and sets, curtains down. That was it.

The core of the book is the collision between two federal entities. One is this Federal Theatre Project. The other is the House Un-American Activities Committee. You know, we think of McCarthyism as the beginning anti-American political interest in Congress. But long before McCarthy came to power, a man he called the greatest communist hunter of all time, Martin Dies of Texas, had been the first to run the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was a short-term committee only supposed to last for seven months. It lasted until 1975 as a permanent congressional committee.

But the story I'm telling is a story between those who were hunting un-Americans and this theater which was the soft underbelly of the New Deal and more easily attacked at a time when FDR was still incredibly popular.

The question that remains unanswered at the end of my book is how do you have a national theater and somehow shape or control the message of that theater?

And that's a very, very hard question to answer. What you have in 1938 is a congressman attacking this theater as a way of attacking and weakening the president's agenda because Roosevelt had taken a really progressive turn in the last couple of years before this. And those, especially Southern Democrats who wanted the status quo on race, were eager to push back, but in a way that wasn't obviously a rejection of FDR himself. So, in a way, the Federal Theatre was collateral damage.

It was the first New Deal initiative that was killed. And we're now down to seven that are left. We no longer have a Federal Theatre because when it came down to it, after seven or eight years of paying for relief, American taxpayers were tired of bailing out the unemployed.

There were congressmen who said -- and even the New York Times said -- actors should eat. They don't have to act. We'll just give them money. It would have been cheaper to have a welfare payment than a work payment.

Gallup was taking the pulse of Americans on various initiatives. And one of the initiatives they explored was this un-American Activities Committee. Americans loved it. They wanted to renew Martin Dies for another season. It was entertainment. In a way, the political theater he was offering was more exciting than the theater productions were offering to Americans. At least at that moment.

Octavian Report: Do you think it was a mistake to put on political productions with taxpayer money?

Shapiro: I actually don’t know the answer to your question because there are so many moving parts. Many people on the left, whose identities are not mainstream, gravitate to the arts because they find a home there. In the 1930s, many, many people who were progressive were gravitating to theater.

We also have to remind ourselves that history did not begin in the United States in the 1960s. The culture wars did not begin then. And the tension between the left and the right certainly didn't begin then. And we would be well advised to look to the 1930s if we're going to be engaging in battles over social security and over the arts in the months and years to come.

Everything was political. Hitler was grabbing Czechoslovakia, invading Poland. Stalin made a pact with Hitler. Communism was making inroads in the United States. Stormtroopers were holding rallies in Madison Square Garden. This was something that Americans could not avoid. It's not something they were simply reading about. And Congress felt that it was important to look into this.

“Was it too political? Yes. But whatever they would have done would have been unacceptable.”

Martin Dies in his House un-American Activities Committee had zero interest in Nazis and communists, because that would take a lot of money and a lot of investigators to go after. But you only needed a couple of people to investigate the Federal Theatre and he found them and ran with that.

Octavian Report: And there were some bad actors there, correct?

Shapiro: Absolutely. But Hallie Flanagan did her best to chase them out. And legally, she couldn't ask anybody, “Are you a communist?” Because it was legitimate to be a member of the Communist Party at this time. So it was a fraught political moment. Many, many, many people who would see themselves as, say, liberal democrats today might be fellow travelers or even card-carrying Communists in the 1930s and it didn't carry the stench that it did in the 1950s and subsequent to that. You have to take sides. Paul Robeson said artists must take sides. And that was what was going on at this moment.

Was it too political? Yes. But whatever they would have done would have been unacceptable. In other words, other parts of what was called Federal One: there was the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Writers Project, a music project that gave music lessons to kids and put on concerts, painters, photographers, research into slave narratives. The whole New Deal arts program was extraordinary. It all got shut down. Just the Federal Theatre got shut down first.

Octavian Report: How do other democracies think about funding the theater?

Shapiro: Last spring, I had won the Berlin Prize and was at the American Academy. So I got to spend four months going to the theater and doing some writing and finishing this book in Berlin. And I'd go to the theater. It would cost about the cost of a latte and a croissant to go to see a play. And I'd be maybe the oldest person in the room because the play was packed with 20-year-olds who could afford to see it.

Many of these plays were about topical subjects like German-Ukrainian tensions in the Second World War and today. It was amazing. And it was all state-subsidized. There was even an English-speaking theater doing first-rate Beckett that the German government supported. That would not have that support in England, Ireland, Scotland, or the United States or Australia.

“We just don't think of theater and the arts any longer as essential to our national health.”

So there are countries, and Germany is one of them, that understand the need to support the arts. But in every one of these countries right now which is facing a right-wing pushback, including Germany, there are moves to cut funding for the arts. So living at another one of these moments where the larger political wars are seeing the arts as casualties or collateral damage to more fundamental collisions between the left and the right.

Octavian Report: Why do you think theater is important for our country?

Shapiro: It's a funny thing. We used to be a nation where people would go to churches and synagogues. Globally, really. We used to be a world in which people were more devout.

Theaters, concert halls, Taylor Swift concerts are places where people gather and feel a connection to each other. I can go to see a play off-Broadway or in Edinburgh and I'll be sitting with people who are strangers who are sharing a collective experience. We're all in our silos. We're all on our laptops or computers at home speaking to like-minded people. Theaters bring us together, expose us to ideas that make us feel uncomfortable.

Ayad Akhtar just put on a brilliant play at Lincoln Center about AI called McNeil. And it forced me to grapple with sides of AI that I had not grappled with. This is what theater can do.

Theater costs money. Somebody has to pay actors. Somebody has to rent the theater space. Somebody has to take tickets. Somebody has to seat you. It's not for free. But nobody ever said democracy was for free anyway. We pay for a military to protect it. We pay for industry to provide that military with what it needs.

We just don't think of theater and the arts any longer as essential to our national health.

Octavian Report: How does the government navigate the idea of federal support for a dynamic theater or public broadcasting without censorship where you may in fact have politicians attacked by the very entities they are funding?

Shapiro: That is the $64,000 question. When a congressman on Dies’ Committee objected to a specific passage in a play, Hallie Flanagan said, “well, we were just quoting you verbatim from the Congressional Record,” which was the truth. That wasn't an adequate answer for him. And they say, why are we wasting federal money on this?

And I guess the answer has to be theater is always going to disappoint or anger somebody. That's in the nature of theater. Aristophanes knew it a long time ago. Shakespeare and his contemporaries knew it a long time ago. And they walked a very careful tightrope trying to avoid punishment and censorship. That is the price we pay for theater. It's going to offend someone.

And the trick is to have leadership there to make sure that the offensiveness or what's disturbing and challenging to a status quo doesn't go too far. There's no question that a number of these productions went too far. They went too far for Hallie Flanagan who would call people in and chew them out, saying you're going to hurt the whole program if you keep pushing these radical stories. So as in anything, if you go too far, you're in trouble.

The Federal Theatre did not go too far. Its opponents hunted it down and blew it up and exaggerated every small excess. You have senators and congressmen standing up, reading the titles of plays. The Vicar's Wife. She Stoops to Conquer. Making everything sound salacious, making everything sound elitist. That's the way these battles were fought and are being fought.

Theater people are really good at putting on plays. They're not really good at defending what they're doing.

I write at the end of the book that Martin Dies begat Joe McCarthy, who begat Roy Cohen who begat Trump who begat, I suppose, the state of affairs in Florida today where there is book banning and constraints on whether Romeo and Juliet can be taught in schools anymore.

“Theater is always going to disappoint or anger somebody….The trick is to have leadership to make sure the offensiveness to a status quo doesn't go too far.”

Where do you stop? Where do you fight back? Where do you draw a line? I was at the Charleston Literary Festival a couple of months ago and a journalist came by and she asked me to speak about the issue in front of the legislature there. They were considering banning Orwell's 1984 and Romeo and Juliet on the grounds that they were politically disturbing and, I think, in the latter case offensive with sexual content.

And it just kind of blew my mind. I know the numbers on teenagers who view pornography is about seventy percent right now. And they're afraid somebody's going to quote Mercutio’s dirty bit in Romeo and Juliet?

So sure there are excesses but there are excesses on both sides. So how do we find some way of preserving a democracy and preserving the arts that everyone can live with?

Octavian Report: Are you worried about PBS and NPR and the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities?

Shapiro: I think right now they're in trouble. And there are two ways of thinking about this. The naive way is thinking, oh, Americans will miss it and call for its return once they lose public radio, once they lose all these wonderful and gifted programs. Programs that keep on giving.

But the truth is with the Federal Theatre, Americans forget pretty quickly. And when it's gone, it's gone. It's much easier to destroy a program than to find the political will and the money and the personnel to keep it going.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Octavian Report is a reader-supported publication of ideas giving voice to experts and original thinkers on a wide range of topics. We believe in the importance of an editorial filter, decorum, nuance and healthy debate. Please join the community, spread the word, and join the conversation!

Interesting history, thanks. Can see why he focused on that history for a book project.

Theatre and listening to radio programs used to be “Everyman” activities 80-100 years ago. Theatre was supplanted by films (as noted) and now films supplanted by the internet and streaming content.

The reality is that the niche audiences that listen to NPR and attend theatre productions are older, richer, white people. They don’t need the government - they should themselves be patrons of whatever content they like. There might be less waste, too. Does the Kennedy center head need to make 1.4 million, and have 10 people on staff making $400-$500k, none of whom create any art at all? To use a British expression - that’s just taking the p*ss. Did Orson Welles need to have a team of millionaire administrators and nepo babies to produce “Voodoo Macbeth”?