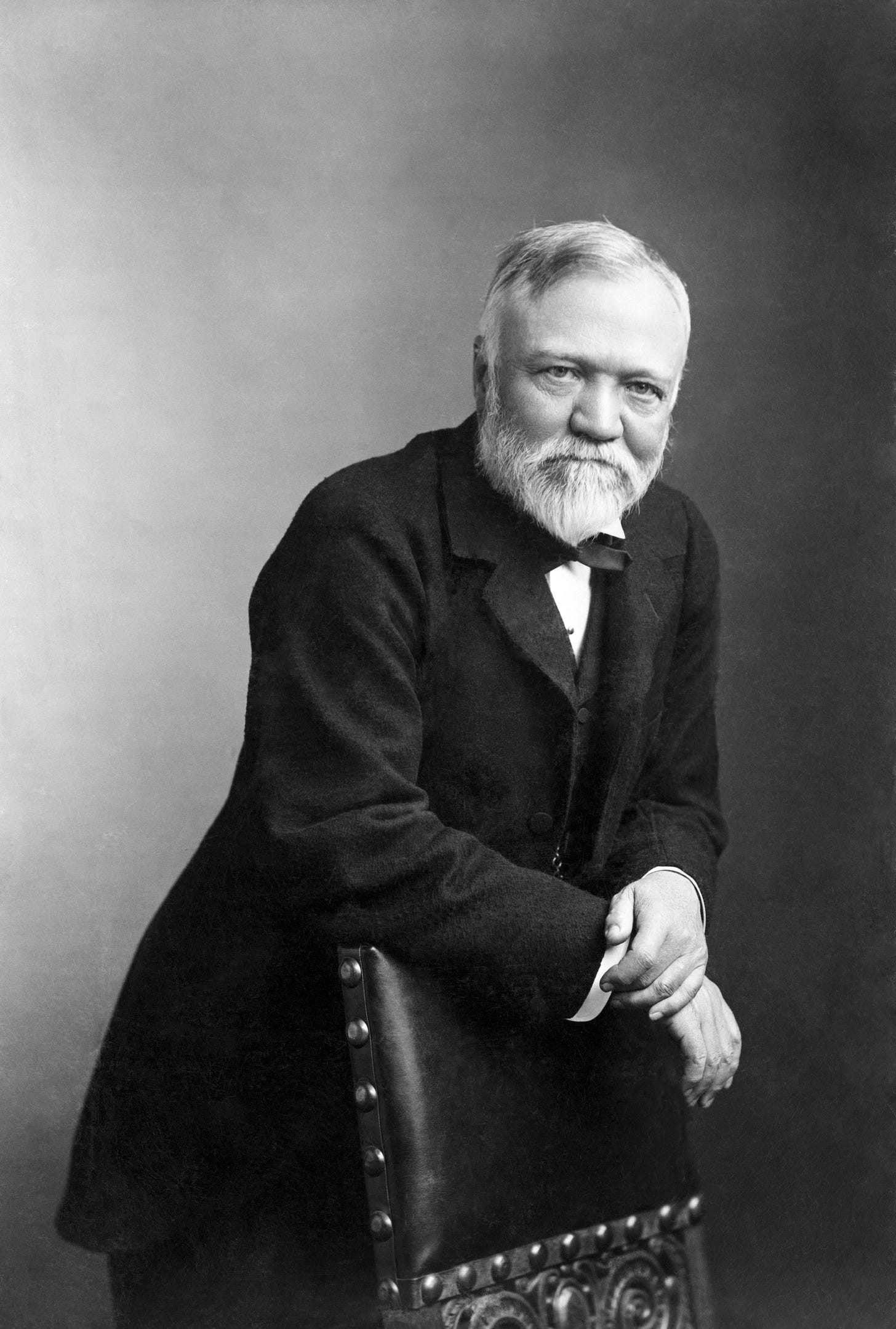

Take it Easy: David Nasaw on the Work Habits of Andrew Carnegie

"For Carnegie, at one point the world’s richest man, and many of his robber baron colleagues, diligence, perseverance, and industry were virtues to be preached—not practiced."

IDEAS

As Omicron recedes and America unmasks, many businesses are finally returning to the office—for real this time. So as part of our occasional series on leadership, we decided now was a time to revisit the work habits of some of America’s most successful entrepreneurs. To do so, we turned to David Nasaw, a historian and the prize-winning biographer of Joseph Kennedy, William Randolph Hearst, and Andrew Carnegie. In the essay below, he looks at the daily routines of some of America’s Gilded Age titans and makes a surprising discovery: they spent a lot less time at work than we do. There may be a lesson there.

Historically, there is something quite curious about the all-encompassing work ethic of many of today’s masters of the universe. For Andrew Carnegie, at one point the world’s richest man, and many of his robber baron colleagues of the Gilded Age a century ago, diligence, perseverance, and industry were virtues to be preached—not practiced. The successful man of business was not a wage slave, paid by the hour or the day or the task, and he should not behave as if he were. Manually laboring drudges might work long hours without sacrificing productivity, but businessman could not. Their work required imagination, thought, calculation.

“Your always-busy man accomplishes little;” Carnegie wrote in 1883, “the great doer is he who has plenty of leisure. Moral: Don’t worry yourself over work, hold yourself in reserve, and sure as fate, ‘it will all come right in the wash.’” The American penchant for delaying gratification, for putting off retirement, for working ceaselessly, for refusing or canceling or postponing or cutting short vacations was, the Scottish-born Carnegie believed, monstrously self-defeating. It sapped the creativity the man of business required to move forward. Americans, he remarked to his cousin, “were the saddest-looking race … Life is so terribly earnest here. Ambition spurs us all on, from him who handles the spade to him who employs thousands. We know no rest. … I hope Americans will find some day more time for play, like their wiser brethren upon the other side.”

Carnegie was not alone in preaching a gospel of leisure. In his autobiography, Random Reminiscences of Men and Events, John D. Rockefeller—who accumulated a fortune estimated at $1 trillion in today’s dollars—admitted almost as a point of pride that he too “was not what might be called a diligent business man.” Though he had, as a young executive, punctually arrived at the Standard Oil offices in Cleveland at 9:15 every morning, he usually spent no more than “three hours a day” there. “He worked at a more leisurely pace than many other executives, napping daily after lunch and often dozing in a lounge chair after dinner,” writes his biographer, Ron Chernow. “By his mid-thirties, he had installed a telegraph wire between home and office so that he could spend three or four afternoons each week at home, planting trees, gardening, and enjoying the sunshine.” At age 50, complaining of fatigue, he withdrew from work for several months. A few years later, he retired completely. “I’m here,” he told an interviewer who asked about his remarkable longevity, “because I shirked: did less work, lived more in the open air, enjoyed the open air, sunshine and exercise.” Even during his working years, “which lasted from the time I was sixteen years old until I retired from active business when I was fifty-five,” Rockefeller admitted that he had “managed to get a good many vacations of one kind or another.”

Carnegie too balanced his adult years carefully between work and leisure. At age 27, while still an employee of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, he wrangled a special leave of absence so that he could spend three months on vacation in Scotland and Europe. Three years later, at age 30, he left his business interests in the hands of Tom, his younger brother, and toured Europe for a year. In 1878, he took another year off to travel round the world. “Carnegie was never a hard worker,” observed his authorized biographer. “Not a hard worker, that is, in the grindstone sense; he spent at least half his time in play, and let other men pile up his millions for him.”

For Carnegie and Rockefeller, part of the magic of twentieth-century capitalism was the disconnect between work and riches. Capital invested wisely in plant, properties, and securities grew and paid dividends, and did so, almost by itself. For Carnegie, the child of a self-employed artisan, this was a revelation. “I shall remember that check as long as I live,” Carnegie wrote in his autobiography, describing his first dividend from the Adams Express Company, a freight-delivery service he held stock in. “It gave me the first penny of revenue from capital—something that I had not worked for with the sweat of my brow. ‘Eureka!’ I cried. ‘Here’s the goose that lays the golden eggs.’”

Carnegie was so excited by the check that before cashing it, he showed it to his friends at their Sunday afternoon gathering. “The effect produced … was overwhelming. None of them had imagined such an investment possibility. … How money could make money, how, without any attention from me, this mysterious golden visitor should come, led to much speculation upon the part of the young fellows, and I was for the first time hailed as a ‘capitalist.’” There was something magical about a poor boy receiving money without having to work for it. Carnegie had not “earned” his dividend check. Yet here it was, in a white envelope lying on his desk, and no one was going to take it away.

Watching over one’s investments and one’s company’s investments took time and effort, Carnegie would learn—just not a whole lot of it. At age 34, he moved away from Pittsburgh, the center of his business enterprise, to New York, the center of his leisure interests. He would, for the rest of his life, carry on his business from New York and his various homes in Scotland, where he spent at least three or four months every summer—and this at a time when the fastest form of communication was the telegraph. He did not attend board or management meetings or visit his mills or communicate on a daily or regular basis with associates, subordinates, business colleagues. He had detailed cost sheets delivered monthly by U.S. mail to his home in New York City, where he marked them up and sent them back to Pittsburgh, with lengthy memos attached. He set long-term strategies for his companies, chose his associates wisely, secured political and business alliances, as needed for expansion, and never took his eye over the profit-and-loss statements.

When A.B. Farquhar, a Pennsylvania businessman, boasted that he was in his office every morning “by seven in the morning” and was the last one to leave in the evening, Carnegie laughed at him. “You must be a lazy man if it takes you ten hours to do a day’s work. … What I do … is to get good men, and I never give them orders. My directions seldom go beyond suggestions. Here in the morning I get reports from them. Within an hour I have disposed of everything, sent out all of my suggestions, the day’s work is done, and I am ready to go out and enjoy myself.”

Andrew Carnegie had learned, early in his business career, that no individual was indispensable nor irreplaceable. The corporate model was a wondrous creation. Its successful operation required a firm division of labors. Success depended on the effective delegation and coordination of leadership functions and responsibilities.

Carnegie never apologized for his success as a businessman nor for the millions upon millions he had made. Business was not for him the highest calling a man might answer. Carnegie loathed being referred to or honored as primarily a businessman. He had left Pittsburgh, a city that was too intent on business, for New York City, the cultural and literary capital of the nation. He intended to use his leisure to educate himself, to make the acquaintance and learn from the premier intellects of his day: from Mark Twain, Herbert Spencer, and Matthew Arnold; to attend lectures; to become an intellectual, a wise man, and an author.

His gospel of leisure enjoined him—and others outside the realm of wage slavery—to behave as free men ought to. The wage slave had no choice but to dedicate his life to work and hope that there might be time left over for leisure. But Carnegie—and Rockefeller—chose to order their lives such that large portions of their waking hours might be dedicated to leisure, not as an escape or alternative to work, but as an end in itself. The rich man could afford to depart from the everyday world of work and business for something far more exalted, the world of leisure.

The irony of ironies was that, instead of moving forward into this brave new world of leisure, as Carnegie had, too many businesspeople, in Carnegie’s day and in our own, have voluntarily imprisoned themselves in the work world as if they too were wage slaves with no alternative but to work their lives away.

Can you let me know the source of this edited portrait of Andrew Carnegie, please? Need to use it in a book.

This “essay” is cloying, obnoxious and insensitive in its wide-eyed admiration for the .01% of either era. Who is Nasaw imagining he’s writing to? Why would Octavian publish such a one-sided, irony-free article? PKuntz