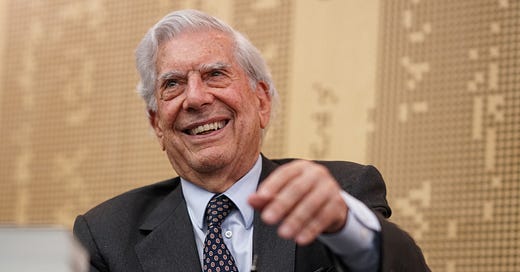

Our conversation with Mario Vargas Llosa

The Nobel Laureate passed away on Sunday, his legacy and insights live on.

With the passing of Mario Vargas Llosa, the world has lost one of its most vital literary voices — a giant of letters whose fiction and essays shaped global thought on democracy, politics, and the human condition. We are proud to publish in full our wide-ranging interview with the Nobel Laureate, Peruvian politician and global thinker. In it, Vargas Llosa speaks with The Octavian Report about the novel as an art form, the dangers of populism and mass media, the fragility of democratic culture, and the enduring power of literature. His insights remain as resonant as ever.

Octavian Report: You seem to regard the 19th Century as a golden age for the novel — why?

Mario Vargas Llosa: For literature, the 19th Century was, I think, an exceptional century.

Look at the great English writers, French writers, Russian writers, and also some American writers too. In Latin America, there were no very great writers with the exception of Sarmiento. Sarmiento was a great writer, but the greatest writers in Latin America were in the 20th Century. I am a great admirer of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and the French writers who have marked me deeply. Victor Hugo and Les Miserablés, principally. And Flaubert, who was a real master for me. Because — unlike Victor Hugo — I think Flaubert was not a genius when he started as a writer. He fabricated his genius with effort, with perseverance, by trying to overcome his limitations. In this sense, he’s a model for writers who are not born geniuses.

Octavian Report: How was he able to do that?

Mario Vargas Llosa: Perseverance. This idea that you can always improve what you have done if you have the will and the critical experience. To try to reach a superior standard of quality in language and also in the structure of the stories. He wasn’t an imitator of the great writers of his time. But he had the critical experience to know that he was not achieving what he wanted to achieve as a writer. And so he persevered and persevered, rewriting and correcting. A desperate fight against his limitations.

He reached genius, and he produced Madame Bovary, L’Éducation Sentimentale, even Salammbô.

I love Salammbô. Critics consider it a minor work, but I think that the elegance and power of the prose, of the language, are able to make his story of Salammbô so romantic. A living story. Flaubert helped me when I was starting to become a writer.

Also Balzac: the ambitions of Balzac. The idea that a novel can embrace society and describe everything that is seen in a society — good, bad, awful, terrible, grandiose. I think in Spain we also had great writers in the 19th Century. Probably the greatest Spanish novel, Fortunata y Jacinta by Pérez Galdós, was written in the 19th Century.

“Flaubert was not a genius when he started as a writer. He fabricated his genius with effort, with perseverance.”

Octavian Report: Have we lost the ambition that novelists had in the 19th Century to do something all-encompassing?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I am absolutely sure of it. The novel is the literary genre of the 19th Century. The greatest novels in history probably were written in the 19th Century.

At that time, people felt that their world was collapsing. It’s this period in which we have this méfiance, this distrust. Méfiance: an act of fate in the real world, in which the fictitious worlds of the novel reach their greatness. And in the 19th Century, this feeling was in Russia, in France, in all Europe; precisely at that time, the greatest novels were written.

Octavian Report: Do you feel that the 19th Century was also a high point for visual arts and music?

Mario Vargas Llosa: No. I would say that the greatest painters were at the beginning of the 20th Century.

The great revolution in art was Picasso, it was cubism, it post-Impressionism. Expressionism in Germany. This is, I think, the beginning of modernity in the visual arts.

Octavian Report: It seems that the Lost Generation doesn’t speak to you as much as it used to. You said sometimes when you reread —

Mario Vargas Llosa: The Lost Generation?

Octavian Report: Hemingway. Fitzgerald.

Mario Vargas Llosa: This was a great generation.

Hemingway, Faulkner. I admire Faulkner enormously. I think he’s probably the writer of the 20th Century, the only one you can compare with the greatest novelists of the 19th Century.

Faulkner wouldn’t have been possible without Joyce, but I think he overcame the master and he created a saga which is even better, more interesting, more deep, more profound than the saga of Ulysses. Or even Proust, whom I think is a great, great novelist. But I don’t think you can compare them with the extraordinary richness of the world that Faulkner was able to produce.

“This idea that once, in the past, there was a homogeneous society — this is a fantasy. It never existed.”

Octavian Report: Do you see any explanation for the fact that Spain produced two of the greatest creative minds — Picasso and Cervantes?

Mario Vargas Llosa: Spain and Latin America produced particularly creative worlds. Philosophy is not a Spanish idea. We have Ortega y Gasset, a great thinker. Philosophy is not a Spanish cultural idea.

But creativity is, without any doubt. Something that is more emotional than intellectual. This is Spain. This is Cervantes. This is Picasso. This is Góngora. This is Guerrero. This is also Latin America.

Latin America has produced fantastic writers, like Borges, like Cortazar, like García Márquez — but not great thinkers. Great thinkers are much more German, or French, or even English. But Latin America and Spain are much more emotional in their creativity. Picasso is a radical expression of this Spanish quality. He was not able to explain anything that he did, but he was a genius at doing things.

His ideas were lacking. They didn’t exist. He had this instinct, which was the instinct of Góngora.

Góngora couldn’t explain what he had done, what he was doing. And he produced the most important and original poetry of his time.

Octavian Report: Picasso maintained close friendships with poets, like Guillaume Apollinaire —

Mario Vargas Llosa: Apollinaire was very intelligent.

Picasso was not intelligent. He was instinctive.

He was a genius by instinct, but when he tried to explain, he was totally confused.

Octavian Report: Do you think there will still be great composers?

Mario Vargas Llosa: Probably. I wouldn’t say great. They are the composers of our time, but they are totally unknown by the common public. Specialists know and follow what they do. Why? Because in our time, unfortunately, there is an extinction of culture — without any doubt because of the great technological revolution in communication. From this has come the frivolization and banalization of culture.

Now, philosophers will defend this. I think for the first time in history we have a democratic culture, but this democratic culture is superficial and frivolous. Without substance. Without many ideas.

I think this is because ideas have been replaced as the main vehicle for culture by images. The book has been replaced by the screen. The result of all this is that we have a democratic culture, because it reaches enormous sections of society. But what it represents is superficial, frivolous, and banal in comparison with what culture was in the past.

“ideas have been replaced as the main vehicle for culture by images”

This is a serious problem, and we have yet to decide if we think that images can replace ideas as the hegemonic instrument of culture.

I think not. I think ideas are more important than images, and that we should arrange through education and through complementary efforts to give profundity to ideas again if we don’t want democracy to collapse. I am absolutely convinced that culture is important for creating the kind of citizens necessary for a democracy — those with critical experience who won’t be manipulated easily by the powers of this world. On the contrary, I think a society impregnated with images and educated only by images can be very easily manipulated by populism. I think it’s happening in the world today. Even in the United States. We thought that the United States was totally vaccinated against populism. In fact, it’s not. It has surrendered to populism, as England has. I lived many, many years in England, and I have enormous admiration for the civic qualities of the English. And look now: Brexit.

Nationalism has produced the kind of populism that is behind Brexit. Our love of images is behind the nationalism that is appearing in Europe. In France, in Italy. The government now in Italy is populist. I think this is a serious situation.

We thought that after the collapse of Communism, democracy would flourish everywhere. But now within democracy we have populism. And its worst expression, which is nationalism, is challenging the democratic institutions and the democratic culture in a way that probably is more sinuous and more difficult to defend against than in Communist times.

Octavian Report: Why is today’s Left seemingly so attracted to authoritarianism?

Mario Vargas Llosa: It’s not serious. I don’t think a serious Left would be nostalgic for the Soviet Union, for the China of the Cultural Revolution. That would be grotesque. The Soviet Union collapsed without foreign intervention because it was totally unable to satisfy the most elementary wishes of the population. I think Communism is dead. For whom, assuming he is in his right mind, could North Korea, or Venezuela, or Cuba be the model of the future? I think these are failed societies, failed governments. So the Left now tries to accommodate itself within the spectrum of democratic institutions.

The problem, I don’t think, is Communism anymore. That, I think, is finished.

The problem is populism. This is a kind of illness that has reappeared within the democratic system and is doing deep, deep damage even in what we thought were the most solid democracies in the world. Britain, France, and America. We cannot close our eyes. The enemy is there, and he is an enemy of the democratic culture, of all its great achievements. So we must keep fighting.

Octavian Report: What can we do to address this problem?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I think we must try to replace images with ideas. I think ideas are essential. And the best way to defend democratic values is replacing these images and fake news. Because fake news, I think, comes with this hegemonic role that images now have in our culture.

Octavian Report: Can this be done, given the brief attention spans that most people have now?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I am not against films and TV series at all. On the contrary. But I think books are more important than images. I think the real, powerful ideas are in books.

I think we must try to rescue reading, rescue the book in this world of images. I think it’s important that we try to recalibrate this relationship, in which my impression is that books are regressing and regressing and regressing, defeated by the world of images. Particularly among young people.

“We must try to rescue reading, rescue the book in this world of images.”

Octavian Report: You once remarked that “History and literature are like brothers.”

Mario Vargas Llosa: I think literature is a complement. When we read Tolstoy we believe that the Napoleonic Wars in Russia were as he described. And even if they were incorrectly described in War and Peace, these ideas — these literary fictions — will prevail over history. It’s literature which gives, let’s say, the most enduring idea of what has happened in history.

Octavian Report: As a novelist who has drawn upon real events as inspiration, how much do you feel obligated to stay with the truth of what actually happened?

Mario Vargas Llosa: When I use history as raw material, I don’t try to be respectful of history. Not at all. I am respectful of literary truth, which is not historical truth. Of course, you cannot distort things that are evident and obvious. These you have to respect.

But all the details you can enrich in literature — for example, my novel The Feast of the Goat respected the basic facts of the Trujillo dictatorship. But there were things that I couldn’t put in the novel, facts of history which were totally not verisimilar.

I had to eliminate them because the brutality, the stupidity, the cruelty of the real world would have been unthinkable for a literary novel. Because the persuasive power of the novel would have been completely damaged by these enormities committed during the Trujillo dictatorship.

Octavian Report: What fascinated you about Trujillo?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I went to the Dominican Republic for the first time — to make a documentary —about 30 years after the assassination of Trujillo. People were no longer paralyzed by terror, and they were telling things. I was so amazed by things that I heard. I remember particularly a doctor. We became very good friends. He told me that during the Trujillo era, the dictator always did a tour in the country; during these tours, he received as a gift from peasants their daughters. I said, “This is true That peasants were giving Trujillo their daughters as a gift?” And he told me, “Yeah.”

I met one of the assistant ministers of Trujillo, and he confirmed this. He told me, “Yeah, that was a problem for El Jefe because he didn’t know what to do with all of these young girls. He married some of them to soldiers, but it was a big problem for us.” I thought: how was this possible? The level of infatuation of these people with a brutal, corrupt dictator was so extreme. So I started to take notes, and one day I discovered that I was writing a novel.

Octavian Report: Where do your ideas come from?

Mario Vargas Llosa: They come from my creation and invention. But in my case, where my imagination meets images preserved by memory. Memory is important. I don’t think I have ever written a story which was totally invented. I think always I have used memories or images preserved by memories as points of departure for a story.

That was the case with The War of the End of the World, which is a Brazilian story. I was so impressed reading about the Conselheiro, about this religious movement in the interior of Bahia.

I was seduced by the information that I received, and I decided to write a novel. Always, I have had something happen to me that awakes a kind of curiosity. And this is the point of departure.

Octavian Report: Do you work on more than one project at once?

Mario Vargas Llosa: No, only one. I cannot work on two things. I write for a newspaper. That I do twice a month. This is different because these are articles about politics, about social problems, about cultural problems. But I work always on just one book.

Octavian Report: How much of your process is writing and how much is editing?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I rewrite a lot. In this, I follow the example of Flaubert.

Octavian Report: Do you enjoy that more?

Mario Vargas Llosa: For me, the most difficult part of writing a book is the draft version. The first version. But when I start to correct it, I really enjoy it. I can work for hours and hours. I am deeply excited by rewriting, not writing. When I write a draft, I suffer a lot.

Octavian Report: A recent book points out that many writers prefer to work in the mornings. Do you?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I work in the morning. Oh, yes.

Octavian Report: Why is that?

Mario Vargas Llosa: Probably it is because I lived in France eight years and I worked at night. I worked at French Radio Television. And we worked until four in the morning. So the first thing that I did when I woke up every day was write. But even when I was at school, some students liked to study at night and some very early in the morning. The latter was my case.

The best hours are the first ones. In the afternoons, I work also, but I correct, I rewrite, I read, I investigate.

“Culture is important for creating the kind of citizens necessary for a democracy — those with critical experience who won’t be manipulated easily.”

Octavian Report: What are you reading now?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I’ve been reading a lot about Guatemala because I have just finished a novel set there during the years of Jacobo Arbenz and Carlos Castillo Armas. Because of the United Fruit Company there was this war, this invasion. It’s interesting: the leader of the counterrevolution was assassinated three years after the coup. Nobody knows what exactly happened. There are theories, and there are new revelations.

Apparently Trujillo was involved in the crime. He involved himself in the crime as vengeance, because he’s totally grotesque — he didn’t receive a decoration that he wanted from Castillo Armas. It seems totally unthinkable, but it happened.

Dictators react in this way. Trujillo had given money and weapons and (allegedly) personnel to Castillo Armas. He asked three things in return: to be decorated with the Quetzal Order, to be invited on a state visit by Castillo Armas when he was in government, and for Castillo Armas to send to the Dominican Republic a general — a Dominican general — because Trujillo wanted to kill him. Castillo Armas didn’t do any of these three things. So apparently, Trujillo sent his killer to Guatemala to kill the general. If he actually did it is not known. But the possibility is there. There are documents.

Octavian Report: When does the book come out?

Mario Vargas Llosa: The end of October or the beginning of November.

Octavian Report: Are you concerned that we are heading into an era of censorship?

Mario Vargas Llosa: There is this feminist movement, which in essence is very respectable.

I think you’ve got to be blind not to be supportive of people who are fighting against prejudice and discrimination against women. Without any doubt. But there are, within the feminist movement, currents which are completely fanatical. And they want total war between women and men. They are trying to censor literature from the past. I have seen this happening with Nabokov. With this discriminatory attitude, there would be no literature. You could in theory end up suppressing all literature in history, because literature is an expression of the real world — the world in which there is discrimination against and limitation of women. And if you are going to censor this, you will destroy what you are trying to do to better democratic values.

So I think we must be very, very critical of this deformation of feminism, and fight it as an enemy of democratic values. Unfortunately, feminism has reached in certain countries a pitch of intolerance, of extremism, which we must fight in the name of freedom, in the name of democracy, of culture. And this is happening unfortunately in Spain and Latin America. For the first time, I think, this problem is global. It’s in third-world countries, it’s in first-world countries. And I think we must not be manipulated by extremism. Political or feminist or religious or ideological.

Octavian Report: What is it that we need to do to counter these forms of extremism?

Mario Vargas Llosa: It’s very difficult because I think there is present in human beings, even if they are very cultivated, a nostalgia; an idea that once, in the past, there was a homogeneous society. This is a fantasy. It never existed. This idea becomes very pressing, very urgent, when you don’t trust what is going on around you.

Look at what is happening in Europe. The construction of the European Union is fantastic progress. But it is terrifying for people who are not sure of what will come. I think nostalgia is the nourisher of populism, of nationalism. And it has different faces. Brexit in Britain. So-called patriotism in Italy, in France. I think we must be prepared to face these challenges, which can even result in the destruction of democratic institutions.

Octavian Report: Are you worried about the fate of the Western canon?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I think it is important for us to preserve and to learn about this tradition.

Tradition is an essential ingredient of culture.

Education should respect this. I am absolutely against the idea that education should exclusively prepare professionals for modern times.

Without this foundation of traditional culture, contemporary culture would be fragile.

Octavian Report: Are you optimistic?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I am a realist. I don’t think it has any real significance, being an optimist or a pessimist. We liberals don’t believe that history is already written. History depends entirely on what we do. If there are new challenges: well, we have to face them, to be critical of them. And I think we should be encouraged by the idea that the worst enemy of the democratic tradition has disappeared — Communism.

I think all the problems that we face are nothing, really, when compared with the ideas of collectivism and statism that Communism represented. The idea of bringing paradise into history was very difficult to fight. But now this idea is completely defeated. So we should face the new challenges with more enthusiasm because of that. Communism was much worse than everything that now represents a threat to the democratic culture.

“Communism is dead. The problem is populism — a kind of illness that has reappeared within the democratic system.”

Octavian Report: When did you know you wanted to be a writer?

Mario Vargas Llosa: I think it was because of what it represented for me to learn how to read. I’ll always remember: I was five years old and the world opened in such an extraordinary way through reading. Reading enriched my life, giving me the opportunity to go on extraordinary adventures.

I think it was probably the origin of my vocation, this pleasure that I had reading the first book I ever read. I discovered that reading was a way of enriching life. I started very, very early, without thinking of being only a writer in the future.

That was very difficult at that time in Latin America, particularly if you were Peruvian. It was unthinkable that your life would be totally consecrated to writing. But little by little I was pushed in this direction. One day, many years later, I was in Madrid. I had received a grant to do a Ph.D. in Madrid. And then I decided that I would try to be only a writer, that literature would be my major preoccupation, and that I should try to organize my life around it. This decision was important for me. Even if I had to find all kinds of work besides literature. But this idea that literature should be the center of my life was very, very important.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. This conversation took place in 2019.

Great interview, so true !!!