Madeline Miller on the Aeneid

"On every page you'll find something that resonates with the modern world. Virgil was a master of human nature and human psychology."

Classicist and best-selling novelist Madeline Miller is world-renowned for her books — The Song of Achilles and Circe — that reimagine and reshape epic poetry and myth into fascinating, rich worlds while casting an an eye on their resonances with contemporary questions of politics, morality, and society. This scintillating interview on the Aeneid dives deep into Virgil’s artistic and emotional mastery and the intricate cultural underpinnings of his masterwork. And if you haven’t subscribed already to WHY THE CLASSICS? you should click here — that way you’ll never miss our newsletter, hitting inboxes every Thursday.

Octavian Report: What drew you to Virgil, and which of his works do you admire the most?

Madeline Miller: I love them all. But I always have to have the Aeneid first in my heart. I would say that the Aeneid is one of the most amazing pieces of complex, subtext-filled poetry that I have ever read. It functions on so many levels. I think when you compare the Iliad and the Odyssey to the Aeneid, you can really see that oral tradition versus one intellect shaping a poem obsessively over 10 — or maybe more — years, and building in all these very deliberate echoes, resonances, and links between sections. When I was first reading it in high school, I finally understood how to analyze poetry in English by working with Virgil because it was like working with this complete masterpiece of poetry which succeeds at every possible level. It's an exciting and moving story, and an interesting story. It has really big ideas. It's absolutely gorgeously written, both in meter and in how Virgil rings the chimes of the Latin language all the way through. It's a masterpiece of poetry.

I am definitely one of those people who believes that this is not a piece of pure Augustan propaganda, but is in fact in many ways questioning some of Augustus's ideas and message and some Roman cultural methods and ideas. One of the things I find so interesting about Virgil is that he was born into a republic when Catullus could write a nasty, smirking poem about Caesar and not be the worse off for it but he himself had to write the Aeneid with Maecenas and Augustus literally breathing down his neck: funding him, sponsoring him, wanting to see early drafts. I am fascinated by what it means as a poet to go from writing in a republic to writing under an empire — indeed, under the first emperor of Rome — and how he must've felt constricted and watched and aware.

Of course there are moments where you see really fulsome praise of Augustus or of Roman progress; at the same time, Aeneas himself is such a flawed hero. He fails in his mission, which his father gives him at the end of book six: "[Your art] is to rule the people with power . . . to place a custom for peace, to spare the suppliant, and war down the proud.” Again and again in books seven through 12, we see Aeneas fail to spare those who have been made subject and cast down. What does that mean about Roman mercy? I think Virgil tells us at the beginning of the Aeneid. "Of such a weight it was to found the Roman race." This is the story of what the cost was of founding Rome. For me, the implication is always, "It had better be worth it. Here is what had to go on in order for Rome to come into being."

I love all those aspects of it. I love that it ends on such a disturbing note, that it ends with Aeneas in a moment of rage killing someone who has surrendered to him. I know people have made the argument that it's not finished. I believe that is absolutely where Virgil meant to leave it. The Italian poet Maphaeus Vegius tried to write the 13th book, where everything ended happily. But what a great moment Turnus’s death is to end on! If you are going to rule by conquest, that means things might be good for you, but they're not good for everybody.

OR: What do you make of the fact that at the height of its power, Rome was tracing its founding to the Trojans — the losers in the Iliad?

Miller: I think the Romans always felt a little bit inferior to the Greeks culturally, which Virgil acknowledges in that same passage: "Others are going to be better astronomers. Others are going to be better artists, but we're going to know how to rule." I think partially it an impulse to say, "We have a part of this grand history. We have a piece of this story, too.” The Iliad and the Odyssey and the story of the Trojan War were such forces in culture. The Romans wanted to write themselves into that, I think, and be part of it. Of course, there is an interesting question here: what does it mean if you are a huge empire that wants to cast itself as the original underdog? I think that's a very interesting and complicated question with not just one answer.

OR: Do you have a favorite character and/or a favorite moment in the poem?

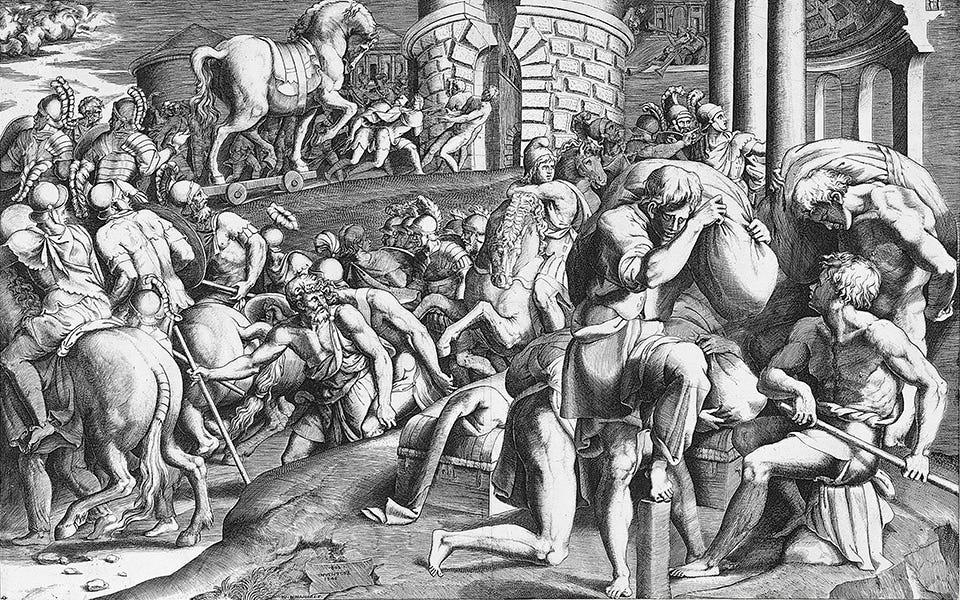

Miller: I think one of the characters that I really appreciate the portrayal of — I will not say I enjoy him because he is a horrendous and morally repulsive character — is Pyrrhus, Achilles's son, who is very memorable in book two. He has an almost comic-book-villain dialogue with Priam where Priam tries to say, "Your father respected me," and he says, "If you don't like it, you can go tell him so. Now die." He kills him in this brutal way. We find out later he has cut off his head and thrown the body on the shore.

Virgil is so good in other places at bringing out the good in his villains, like Mezentius. They have these very human characteristics. We see that Mezentius is a father who loves his son at the same time that he is this terrible enemy. Virgil is, in my opinion, the great humanist. He's always looking to complicate the picture and make the heroes have flaws and the villains have things that make them sympathetic. Pyrrhus is a pure villain, I would say. It's really a terrifying portrait. It's how human nature can become so overfilled with violence and sociopathy that they became like a force of nature. Pyrrhus is a chilling portrait of a person who has no empathy, who has no ability to feel for anyone else other than himself. My portrait of Pyrrhus in The Song of Achilles was very influenced by that. I used Virgil's portrait of Pyrrhus because it spoke to me so, so much as a portrayal of what happens when you get raped by the gods. In my version, he's raped by Thetis.

I, of course, love Dido. I think she is a wonderful character. People have often focused on her as a character who is tragic in love, but some of my favorite parts are the scenes in book one before she and Aeneas really know each other, where we see her in her element as this incredible leader who has survived adversity: her brother murdering her husband, her flight from him, bringing her people safely to a new home, negotiating for land, earning the respect of the people around her. She is building this beautiful, idyllic city in complete, benevolent control of her people. It's such an amazing portrait of this strong woman that it really makes what happens in book four when she ends up killing herself all the more tragic. I love the contrast of what Virgil does there with creating such a great leader but with such psychology. We can see why she — meddling goddesses and Cupid aside — would fall in love with Aeneas. These are two survivors. They've both lost spouses that they dearly loved. They're refugees from their homelands. They have so much in common. It would make sense that they would find kindred spirits in each other.

OR: How much of the Aeneid springs out of Virgil's imagination? How much comes from the repository of Greek and Roman myths?

Miller: A fair amount comes from his imagination. He's drawing on so many sources. There are many moments where he likes to explain the origin for things that they do now in Rome, which his audience must have loved: "Oh, I get that. That's why we do that, because of this thing that Aeneas did." There are lots of moments like that where he backfills the history behind some Roman ritual or Roman holiday.

Even the materials that he's working that are well-represented in myth, like the fall of Troy — even there he is imagining things. Book two is his fall of Troy section. Even within that, it's wonderful to see him inventing; to see the ghost of Hector appear to Aeneas. Now, obviously these are two characters who are well-established in the Trojan myths, but seeing Virgil's version of their interaction and what Hector has to say to Aeneas is fascinating. It's always very interesting to ask "Where is Virgil inventing and how is he changing or speaking back to the myth that was already there, speaking back to Homer?"

One of the moments I love is actually the disputed section where people are not sure if it's really Virgil. Some people think it was added later, but I absolutely believe it's Virgil. It's during the fall of Troy. Aeneas sees Helen hiding as the palace is falling around her, and he has this moment of overwhelming rage where he just wants to kill her. He's aware of the fact that it's dishonorable to kill a woman, but he doesn't care. He says, "I'll be praised for this because she's so horrible." He goes to kill her, and his mother Venus appears and she says, "You don't get it." She pulls the veil of mortal sight away from his eyes and she says, "This is not about humans. This is about the gods. There is a god tearing down the city. Stop thinking about this petty mortal vengeance." I always feel like in Virgil that the gods represent the equivalent of kings and emperors: you guys are fighting down here, but this is where the real power is. You're being manipulated by these larger-than-life powers that you can't even touch.

OR: Why do you think people should read the Aeneid? What do you think people get out of it? What makes it so great?

Miller: As the ancients said, "There's nothing new under the sun." Human nature has really not changed in millennia. The trappings of culture have changed, but the way humans deal with grief and love and war and hope and despair are still the same. I think in a lot of this ancient literature, you see brilliant portraits of human nature. Reading the Aeneid, I think there's so much there that we can connect to modern moments, both in a political sense and in a personal sense, in large and small ways. Here is Aeneas who is thrust into the position of being a leader. He was always used to Hector being in charge. He has to take over and find his way when he feels very unmoored. How do you do that? How do you find your way to a new home?

The Aeneid in particular is all about refugees looking for a new homeland. What could be more modern than that? We are facing a modern refugee crisis, and that is what the Trojans were. They were refugees. I think Virgil tells that story so movingly, particularly in books one through six, of how lost and alone and hopeless and frightened and confused these people feel, completely relying upon the kindness of strangers wherever they go.

On every page you'll find something that resonates in some way with the modern world. Virgil was a master of human nature and human psychology.